Found: Records of Pompeii's Survivors

This story was originally published on The Conversation. It appears here under a Creative Commons license. On August 24, in the year 79, Mount Vesuvius erupted, shooting over 3 cubic miles of debris up to 20 miles (32.1 kilometers) in the air. As the ash and rock fell to Earth, it buried the ancient cities of Pompeii and Herculaneum. According to most modern accounts, the story pretty much ends there: Both cities were wiped out, their people frozen in time. It only picks up with the rediscovery of the cities and the excavations that started in earnest in the 1740s. But recent research has shifted the narrative. The story of the eruption of Mount Vesuvius is no longer one about annihilation; it also includes the stories of those who survived the eruption and went on to rebuild their lives. The search for survivors and their stories has dominated the past decade of my archaeological fieldwork, as I’ve tried to figure out who might have escaped the eruption. Some of my findings are featured in an episode of the new PBS documentary, Pompeii: The New Dig. Pompeii and Herculaneum were two wealthy cities on the coast of Italy just south of Naples. Pompeii was a community of about 30,000 people that hosted thriving industry and active political and financial networks. Herculaneum, with a population of about 5,000, had an active fishing fleet and a number of marble workshops. Both economies supported the villas of wealthy Romans in the surrounding countryside. In popular culture, the eruption is usually depicted as an apocalyptic event with no survivors: In episodes of the TV series Doctor Who and Loki, everyone in Pompeii and Herculaneum dies. But the evidence that people could have escaped was always there. The eruption itself continued for over 18 hours. The human remains found in each city account for only a fraction of their populations, and many objects you might have expected to have remained and be preserved in ash are missing: Carts and horses are gone from stables, ships missing from docks, and strongboxes cleaned out of money and jewelry. The evidence that people could have escaped was always there. All of this suggests that many—if not most—of the people in the cities could have escaped if they fled early enough. Some archaeologists have always assumed that some people escaped. But searching for them has never been a priority. So I created a methodology to determine if survivors could be found. I took Roman names unique to Pompeii or Herculaneum—such as Numerius Popidius and Aulus Umbricius—and searched for people with those names who lived in surrounding communities in the period after the eruption. I also looked for additional evidence, such as improved infrastructure in neighboring communities to accommodate migrants. After eight years of scouring databases of tens of thousands of Roman inscriptions on places ranging from walls to tombstones, I found evidence of over 200 survivors in 12 cities. These municipalities are primarily in the general area of Pompeii. But they tended to be north of Mount Vesuvius, outside the zone of the greatest destruction. It seems as though most survivors stayed as close as they could to Pompeii. They preferred to settle with other survivors, and they relied on social and economic networks from their original cities as they resettled. Some of the families that escaped apparently went on to thrive in their new communities. The Caltilius family resettled in Ostia – what was then a major port city to the north of Pompeii, 18 miles from Rome. There, they founded a temple to the Egyptian deity Serapis. Serapis, who wore a basket of grain on his head to symbolize the bounty of the earth, was popular in harbor cities, like Ostia, which were dominated by the grain trade. Those cities also built a grand, expensive tomb complex decorated with inscriptions and large portraits of family members. Members of the Caltilius family married into another family of escapees, the Munatiuses. Together, they created a wealthy, successful extended family. The second-busiest port city in Roman Italy, Puteoli—what’s known as Pozzuoli today—also welcomed survivors from Pompeii. The family of Aulus Umbricius, who was a merchant of garum, a popular fermented fish sauce, resettled there. After reviving the family garum business, Aulus and his wife named their first child born in their adopted city Puteolanus, or “the Puteolanean.” Some of the families that escaped went on to thrive in their new communities. Not all the survivors of the eruption were wealthy or went on to find success in their new communities. Some had already been poor to begin with. Others seemed to have lost their family fortunes, perhaps in the eruption itself. Fabia Secundina from Pompeii—apparently named for her grandfather, a wealthy wine merchant—also ended up in Puteoli. There, she married a gladiator, Aquarius the retiarius, who died at the age of 25, leaving her in dire financial s

This story was originally published on The Conversation. It appears here under a Creative Commons license.

On August 24, in the year 79, Mount Vesuvius erupted, shooting over 3 cubic miles of debris up to 20 miles (32.1 kilometers) in the air. As the ash and rock fell to Earth, it buried the ancient cities of Pompeii and Herculaneum.

According to most modern accounts, the story pretty much ends there: Both cities were wiped out, their people frozen in time.

It only picks up with the rediscovery of the cities and the excavations that started in earnest in the 1740s.

But recent research has shifted the narrative. The story of the eruption of Mount Vesuvius is no longer one about annihilation; it also includes the stories of those who survived the eruption and went on to rebuild their lives.

The search for survivors and their stories has dominated the past decade of my archaeological fieldwork, as I’ve tried to figure out who might have escaped the eruption. Some of my findings are featured in an episode of the new PBS documentary, Pompeii: The New Dig.

Pompeii and Herculaneum were two wealthy cities on the coast of Italy just south of Naples. Pompeii was a community of about 30,000 people that hosted thriving industry and active political and financial networks. Herculaneum, with a population of about 5,000, had an active fishing fleet and a number of marble workshops. Both economies supported the villas of wealthy Romans in the surrounding countryside.

In popular culture, the eruption is usually depicted as an apocalyptic event with no survivors: In episodes of the TV series Doctor Who and Loki, everyone in Pompeii and Herculaneum dies. But the evidence that people could have escaped was always there.

The eruption itself continued for over 18 hours. The human remains found in each city account for only a fraction of their populations, and many objects you might have expected to have remained and be preserved in ash are missing: Carts and horses are gone from stables, ships missing from docks, and strongboxes cleaned out of money and jewelry.

All of this suggests that many—if not most—of the people in the cities could have escaped if they fled early enough.

Some archaeologists have always assumed that some people escaped. But searching for them has never been a priority.

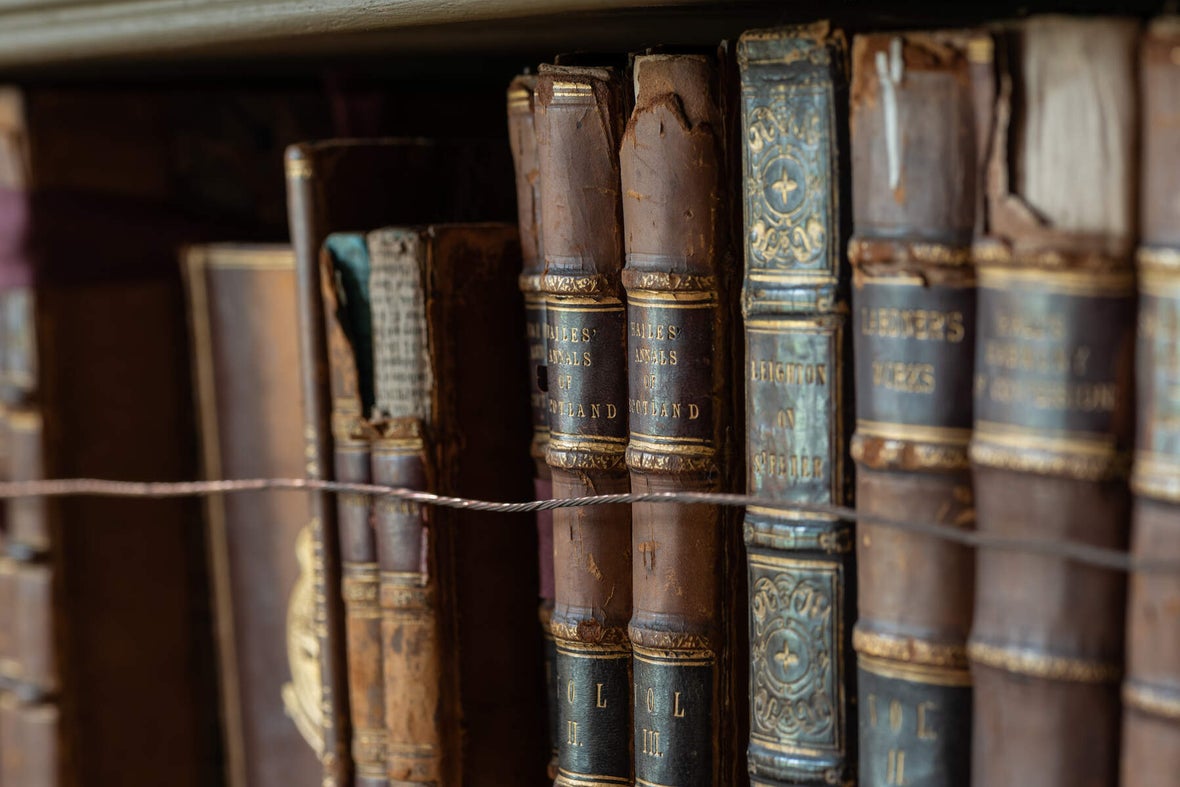

So I created a methodology to determine if survivors could be found. I took Roman names unique to Pompeii or Herculaneum—such as Numerius Popidius and Aulus Umbricius—and searched for people with those names who lived in surrounding communities in the period after the eruption. I also looked for additional evidence, such as improved infrastructure in neighboring communities to accommodate migrants.

After eight years of scouring databases of tens of thousands of Roman inscriptions on places ranging from walls to tombstones, I found evidence of over 200 survivors in 12 cities. These municipalities are primarily in the general area of Pompeii. But they tended to be north of Mount Vesuvius, outside the zone of the greatest destruction.

It seems as though most survivors stayed as close as they could to Pompeii. They preferred to settle with other survivors, and they relied on social and economic networks from their original cities as they resettled.

Some of the families that escaped apparently went on to thrive in their new communities. The Caltilius family resettled in Ostia – what was then a major port city to the north of Pompeii, 18 miles from Rome. There, they founded a temple to the Egyptian deity Serapis. Serapis, who wore a basket of grain on his head to symbolize the bounty of the earth, was popular in harbor cities, like Ostia, which were dominated by the grain trade. Those cities also built a grand, expensive tomb complex decorated with inscriptions and large portraits of family members.

Members of the Caltilius family married into another family of escapees, the Munatiuses. Together, they created a wealthy, successful extended family.

The second-busiest port city in Roman Italy, Puteoli—what’s known as Pozzuoli today—also welcomed survivors from Pompeii. The family of Aulus Umbricius, who was a merchant of garum, a popular fermented fish sauce, resettled there. After reviving the family garum business, Aulus and his wife named their first child born in their adopted city Puteolanus, or “the Puteolanean.”

Not all the survivors of the eruption were wealthy or went on to find success in their new communities. Some had already been poor to begin with. Others seemed to have lost their family fortunes, perhaps in the eruption itself.

Fabia Secundina from Pompeii—apparently named for her grandfather, a wealthy wine merchant—also ended up in Puteoli. There, she married a gladiator, Aquarius the retiarius, who died at the age of 25, leaving her in dire financial straits.

Three other very poor families from Pompeii—the Avianii, Atilii and Masuri families—survived and settled in a small, poorer community called Nuceria, which goes by Nocera today and is about 10 miles (16.1 kilometers) east of Pompeii.

According to a tombstone that still exists, the Masuri family took in a boy named Avianius Felicio as a foster son. Notably, in the 160 years of Roman Pompeii, there was no evidence of any foster children, and extended families usually took in orphaned children. For this reason, it’s likely that Felicio didn’t have any surviving family members.

This small example illustrates the larger pattern of the generosity of migrants—even impoverished ones—toward other survivors and their new communities. They didn’t just take care of each other; they also donated to the religious and civic institutions of their new homes.

For example, the Vibidia family had lived in Herculaneum. Before it was destroyed by the eruption of Vesuvius, they had given lavishly to help fund various institutions, including a new temple of Venus, the Roman goddess of love, beauty, and fertility.

One female family member who survived the eruption appears to have continued the family’s tradition: Once settled in her new community, Beneventum, she donated a very small, poorly made altar to Venus on public land given by the local city council.

While the survivors resettled and built lives in their new communities, government played a role as well. The emperors in Rome invested heavily in the region, rebuilding properties damaged by the eruption and building new infrastructure for displaced populations, including roads, water systems, amphitheaters and temples.

This model for post-disaster recovery can be a lesson for today. The costs of funding the recovery never seems to have been debated. Survivors were not isolated into camps, nor were they forced to live indefinitely in tent cities. There’s no evidence that they encountered discrimination in their new communities.

Instead, all signs indicate that communities welcomed the survivors. Many of them went on to open their own businesses and hold positions in local governments. And the government responded by ensuring that the new populations and their communities had the resources and infrastructure to rebuild their lives.

Steven L. Tuck is a professor of classics, at Miami University.

Koja je vaša reakcija?